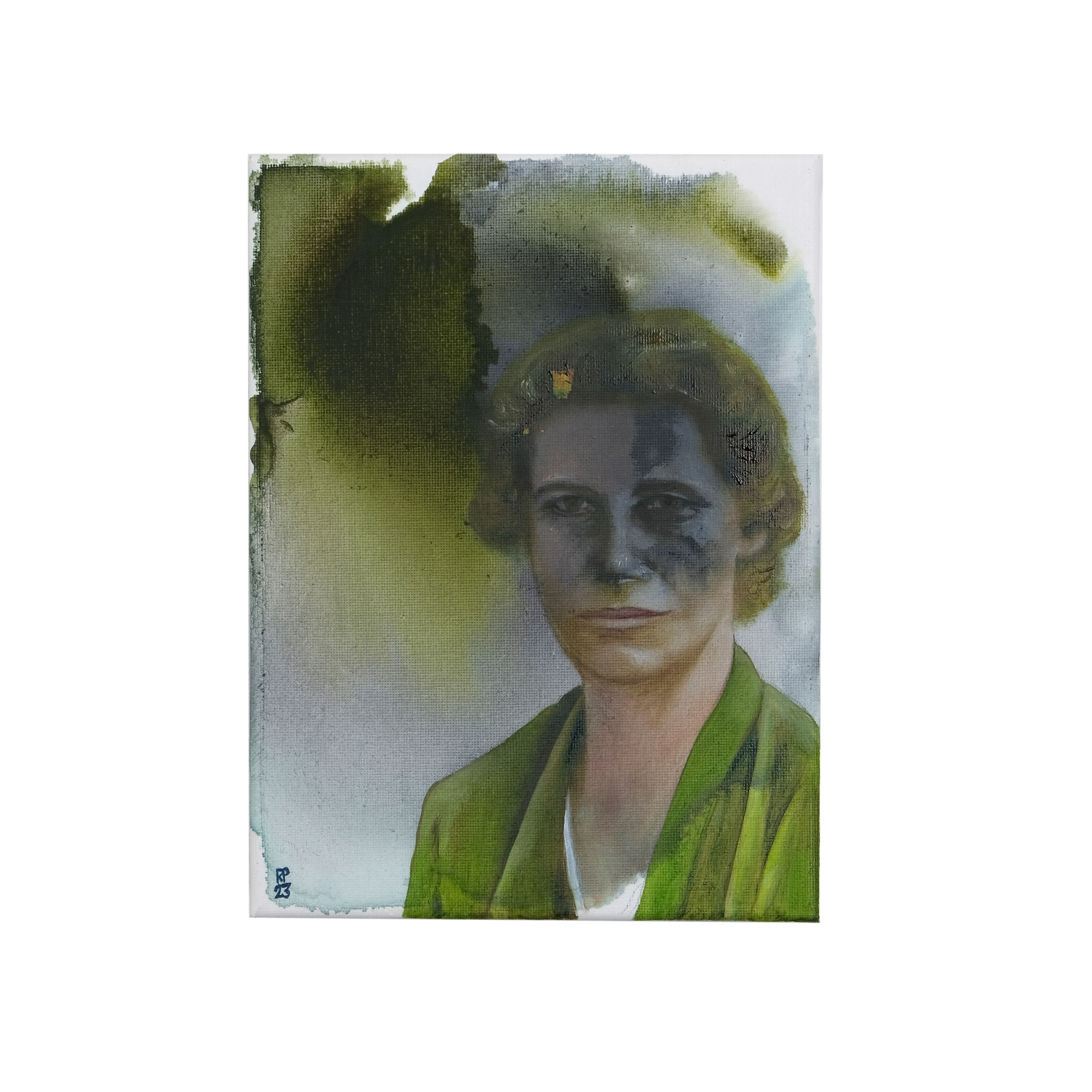

It began with an earthquake (Inge Lehmann)

Availability & Price

More about "It began with an earthquake (Inge Lehmann)"

Inge Lehmann (1888-1993) was a Danish geophysicist and the first dedicated seismologist. She observed deviant waves after a major earthquake in New Zealand in 1929 and then proved in 1936 that the earth must have a hard core - and not, as previously assumed, a liquid magma core. Inge Lehmann researched and published throughout her life, most recently in 1987, when she was almost 90 years old. In an interview, she once soberly stated: "You should know how many incompetent men I had to compete with in vain."

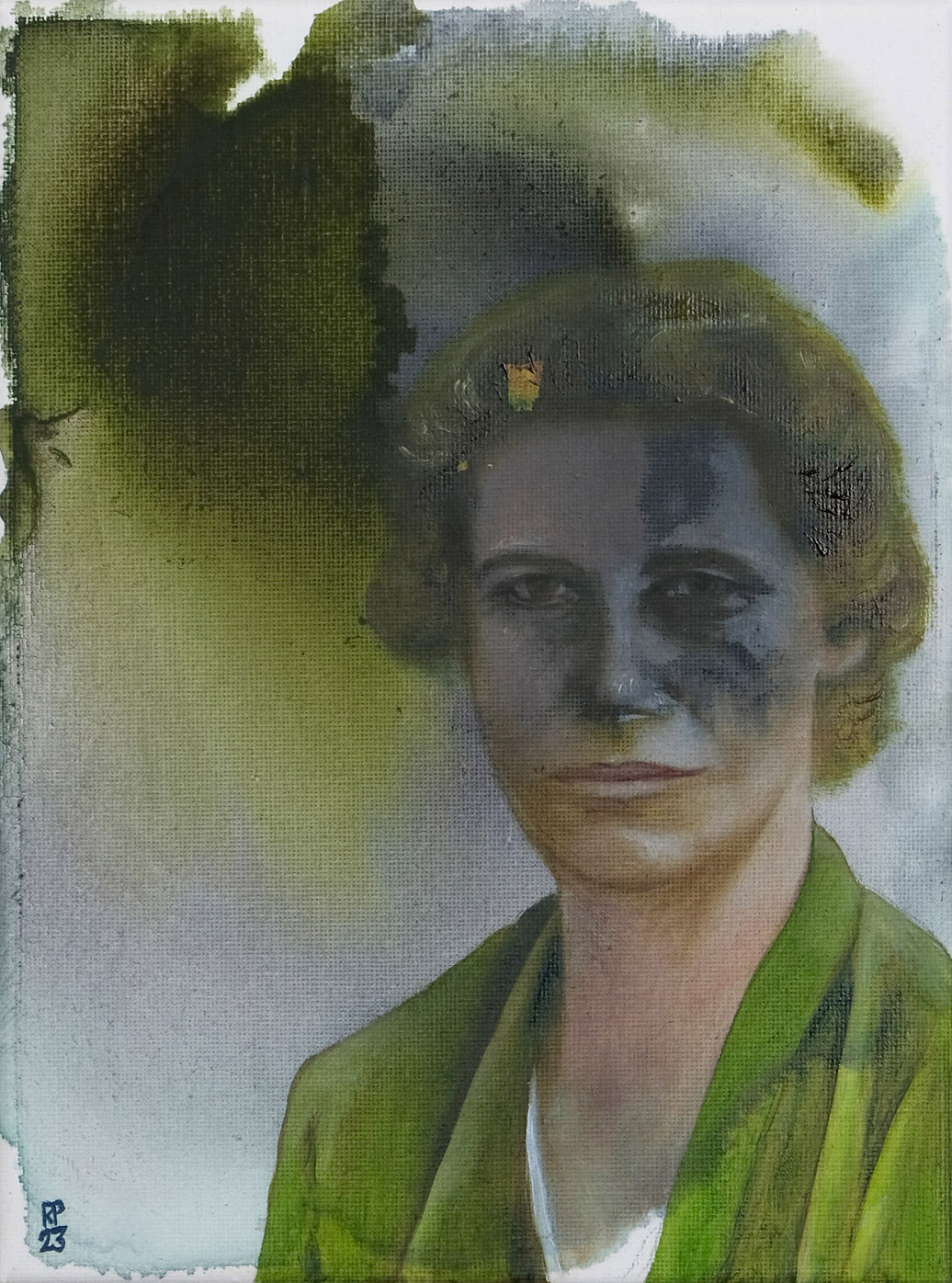

The painting technique of this work

The basis is a white canvas, which initially was colored with ink in a random process. In the next step, the artist paints the portrait on these colored areas. The idea behind this type of representation is the fact that women and their contributions are not seen clearly and unambiguously. The portrait series aims to make women and their achievements - like Inge Lehmann - more visible and thus better known.

About the portrait

This portrait is based on a historical photo of Inge Lehmann from the 1930s - the very time in which she made and proved her most important groundbreaking discovery. The choice of green as the color for her jacket is an artistic interpretation.

Who was Inge Lehmann?

Lehmann, who had studied mathematics at the Universities of Copenhagen and Cambridge, investigated how the energy released by earthquakes moves through the earth. While examining data from a major earthquake in New Zealand in 1929, she discovered that energy waves in the earth's layers, known as seismic waves, occurred in unexpected places.She suspected that they must have been deflected by some kind of boundary in the earth's core.This led her to theorize in 1936 that the Earth's core consists of two parts: a solid metal core surrounded by an outer liquid core, disproving the common theory of a completely liquid core.Despite her success, Lehmann recounted how she struggled against the male-dominated research community, once remarking: "You should know how many incompetent men I had to compete with in vain." In addition to numerous awards and honors for her scientific achievements, a beetle species Globicornis (Hadrotoma) ingelehmannae was named after her in 2015.

| Technique & Materials: | Oil and ink on canvas |

|---|

Login